Guillermo Alvarez: Mexico's Lone Ranger

of Marine Conservation

![]()

|

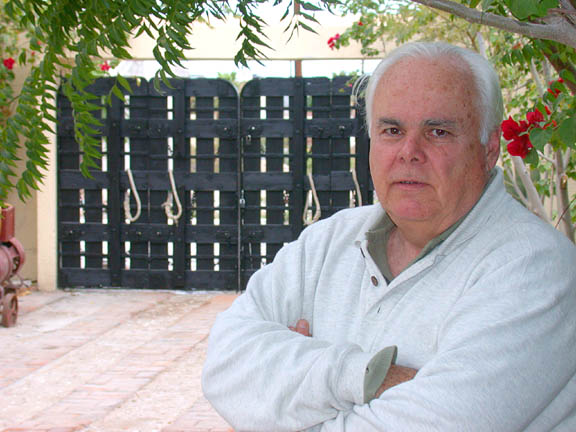

BEEN THERE, DONE THAT -- Guillermo Alvarez at his home in La Paz. In the background are four black-painted "doors," joined together to form a courtyard gate, from Alvarez' boat the San Carlos, which he sold in 1996. The "doors" were deployed underwater to keep nets spread while bottom trawling for shrimp. Photo by Gene Kira |

A LIFE STORY AND FISHERIES CONSERVATION MISSION UNIQUE IN HIS COUNTRY

By Gene Kira, February 28, 2004, as orginally published in Western Outdoor News:

Fifty years ago, Guillermo Alvarez was an eight-year-old boy, swimming and diving daily in the bay near his family’s beach front restaurant in Acapulco, which was at that time a modest Mexican town with a population of about 25,000.

It was an age of technological innocence--less than ten years after the end of World War II--when it was widely believed that science, if not yet quite perfected, was certainly well within reach of solving the world’s problems.

Half a century later, of course, those problems and many new ones besides are still with us, but in 1954 the young Guillermo could certainly have been justified in believing that the brilliance and abundance of sea life that he saw every day in the crystal waters of Acapulco Bay--would last forever.

|

|

Against his father’s wishes, Guillermo decided not to enter the family businesses, but to become a scientist, a student of marine technology and production who would provide seafood not just for a single restaurant, but for the entire world.

He studied chemical engineering at the prestigious Instituto Technologico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey, and then marine science and food technology through an international program developed by the Ford Foundation, Rockefeller Foundation, and the Interamerican Development Bank.

In 1968, he published his thesis at Guaymas, a pioneering study of plankton bloom cycles in the Sea of Cortez, and he began a career that would lead to further studies, and industry and government assignments, in Holland, Spain, Germany, Japan, Mexico, the United States, and eventually, to ownership of his own commercial fishing fleet in Baja California.

But ironically, in the end, Alvarez’ long career led him not to the production of limitless food from the sea, but into a desperate struggle to save what is left of it, and to repair the damage that he and his former colleagues in the commercial fishing industry have wreaked upon the world’s oceans.

“I’ve made a tremendous number of mistakes!” Alvarez declared at his home in La Paz. “I was the one who brought drift gill nets to Baja California!”

Indeed, that personally painful episode in Alvarez’ life, perhaps more than any other, serves to explain the dedication and drive that have made him today Mexico’s most credible and effective marine conservation lobbyist, unique in his technical expertise, high-level connections--and lately--in his emerging influence on federal policy.

After training in a United Nations program in Europe, Alvarez returned to Baja California in 1971 and built not only the San Carlos tuna and sardine cannery at Magdalena Bay, but in the 1980s, a personal fleet of five highly-efficient prototype boats, designed to trawl for shrimp and then switch gear and fish with gill nets.

This concept, developed under a program funded by the U.S. government, worked beautifully, as Alvarez’ multipurpose boats took easy profits on Sea of Cortez shrimp during the lucrative first six weeks of each season, and then moved to the Pacific Ocean to gill net massive catches of white seabass and yellowtail between Ensenada and Magdalena Bay.

But disaster struck almost immediately, as the white seabass and yellowtail were quickly wiped out by combined fleets totaling only 22 boats.

“We depleted the fish,” Alvarez says ruefully. “And we also flooded the market, so the price went down. We were being turned away at San Pedro.

“We realized within five years that it was a huge mistake. We saw the biggest drop in white seabass. It was impressive, criminal.

“On my first trip in 1982, we made a $30,000 cash profit on white seabass. But by 1986, we knew we had blown it. By 1988, we stopped fishing for white seabass and yellowtail. There weren’t enough left, even with sonar and satellite imaging.”

Facing financial disaster, Alvarez attempted to develop alternate, sustainable fishing methods for the Ensenada fleet, but conflicts with reactionary owners eventually led to personal harassment in the form of a false warrant issued for his arrest on trumped up real estate fraud charges, and in 1992, the sinking of two of his boats, the El Moro and Vasamar, in Ensenada, and the subsequent loss of his business.

Said Alvarez, “That broke us. After that, I could not even think about Ensenada without getting emotional and angry. I could not even go near El Sauzal without my heart pounding.”

Alvarez spent the next several years licking his wounds, and doing some serious soul searching that would lead him eventually to his impassioned mission in life: the saving of the Sea of Cortez and the immensely rich biomass contained in the unique California Current System off the Pacific coast.

“That was a period in which I looked into myself,” he says. “I was trying to figure out what to do with my life. A difficult period. I had a terrible taste in my mouth. After all, my career training was to develop the marine resources of Mexico.”

In 1998, Alvarez sold his home in San Diego, and he and his wife moved permanently to La Paz, where he began a full-time career as a marine conservation lobbyist, rapidly making hundreds of contacts, and building alliances and funding for the battles to come.

Six years later, at the age of 58, Alvarez’ star is once again ascendant.

As a unifying Lone Ranger of Mexico’s unruly and highly-fragmented conservation movement, he walks a tightrope every day, working virtually around-the-clock by phone and email, and traveling frequently to meetings and conferences, quietly playing the role of backroom dealmaker and statesman.

The challenge, says Alvarez, is to deal successfully with three radically disparate groups, each with an agenda that conflicts fundamentally with the other two:

• Dozens of highly-idealistic conservationist organizations must be encouraged to keep making noise, even if their propaganda is sometimes less than completely credible.

• Hundreds of desperate commercial boat owners, and thousands of subsistence “ribereño” skiff fishermen, must be convinced to abandon uncontrolled gill nets, long lines, heavy bottom trawling, and reef fish traps--all of which kill many times more “bycatch” than target species.

• An entrenched government bureaucracy must be convinced to reverse half a century of all-out, scorched earth commercial fishing, in favor of a modern, balanced approach that permits controlled, sustainable commercial fishing to coexist with ecotourism and sportfishing.

And the biggest challenge of all, says Alvarez, is to show hard-pressed politicians how to make these “right” decisions without getting themselves tarred and feathered by their own electorates.

Often, this political balancing act seems like the “art of the impossible,” but just recently, the heretofore intransigent federal government has begrudged some amazing concessions. To Alvarez, it seems that a true sea change is now at hand, and he is anxious to consolidate his gains and lay the foundation for further progress before the end of President Fox’s administration in three more years.

The string of recent victories is impressive:

• An all-important and apparently sincere government promise to eliminate drift gill nets and limit long lines in Mexican waters.

• Approval of satellite vessel position monitoring systems to keep commercial fishing boats honest.

• Dedication of millions of dollars per year from the sale of sportfishing licenses to marine conservation.

• Inclusion of the Secretary of Tourism in fisheries management decisions.

• Seats gained on the federal Nautical-Recreational and Sportfishing Commission, the National Fisheries and Aquaculture Council, the State Fisheries Consulting Council, and a new office for tourism and conservation within the Department of Fisheries itself.

• A greatly expanded, increasingly transparent dialogue with new fisheries chief, Ramón Corral Ávila, after the successful ouster of his reactionary predecessor, Jerónimo Ramos.

Although it is difficult to measure the significance of any single individual in the Byzantine world of Mexican fisheries politics, it is patently clear that without Alvarez’ dedication and skill as a lobbyist, very little of this progress could have happened; every significant victory of the past several years has been influenced by his often unseen hand.

For example, in the fall of 2002, Alvarez was instrumental in engineering the defeat of Shark Norma 029, federal legislation designed to allow increased bycatch of game fish under the guise of “research” fishing for shark. A nationwide newspaper campaign of desplegados, or paid public announcements, followed by a public uproar on national television and threats of embarrassing street demonstrations during the international APEC conference at Cabo San Lucas (attended by 21 heads of state), resulted in the hasty cancellation of the proposed law. Politicians were quick to take credit for the victory, but deep in the background, it was Guillermo Alvarez--the unseen Lone Ranger--who had made the first critical phone calls, quickly raising the seed money needed for the original desplegados, before quietly disappearing from the scene. “Who was that masked man?” the department of fisheries must have asked itself.

Whence comes this Lone Ranger’s unique ability to coordinate and get positive results from camps of such seemingly insurmountable disparity? Above all else, Alvarez’ tortured résumé gives him a balanced empathy for the many conflicting points of view that he must deal with on a daily basis. Ever the realist, Alvarez harbors no sacred cows. He seeks politically feasible solutions that will allow equitable, sustained use by all sectors:

• The young boy from Acapulco grieves for his country’s lost marlin, tuna, swordfish, dorado, yellowtail, reef fish, sea urchins, sea cucumbers, abalone, lobster, sea turtles, and all the rest. But nevertheless, he gives short shrift to groups who would eliminate commercial fishing entirely, or who seek absolute protection for pet species. Alvarez seeks sustainable commercial fishing, not its abolishment.

• The failed fleet owner is quick to recognize not only the commercial fisherman’s present pain, but also his past stupidities: “We must develop alternate ways to make a living. This has been a tremendous mistake. Baja’s subtropical Pacific coast and Sea of Cortez are very vulnerable. We have lots of species, but no big biomass of any given one of them. We cannot sustain a fishery here like in Alaska. If you go after any given species, you wipe it out.”

• The internationally-trained fisheries official--who in the 1970s negotiated his government’s implementation of its 200-mile Exclusive Economic Zone with rancorous U.S. boat owners--can say with authority: “A completely new approach is needed. The southern part of the California Current System should be preserved by joint programs between the U.S. and Mexico. It is important to both countries. After all these failures, we must preserve this area, because many species come here to reproduce.”

|

|

Although much progress has been made, Alvarez today feels that he has arrived at another cusp in his career. He has decided that the time is appropriate for him to become more than a guiding referee among the various conflicting forces, and to establish a new organization--the Center for Marine Development and Protection.

In addition to such immediate goals as the drafting of a proper shark norma, Alvarez sees several critical areas that must be addressed:

• Progressive change to Mexico’s outdated fisheries laws.

• True enforcement of those laws.

• Public awareness of the issues.

• Promotion of tourism, already Mexico’s second largest industry, as the ultimate means of making maximum, sustainable economic use of the marine resource.

This Center for Marine Development and Protection, Alvarez feels, will for the first time allow him to set his own agenda, rather than act as a facilitator for other non-government organizations. It will give him the voice he needs to bring his goals to final conclusion.

The historical moment seems to be on Alvarez’ side. Watershed studies, such as the 2003 Dalhousie University report showing a 90 percent decline in major fish stocks, and a report with comparable conclusions soon to be released by the U.S. Commission on Ocean Policy, make it clear that all fishing nations must develop an entirely new model for how the oceans should be used to the greatest benefit.

After a patient, sometimes lonely campaign lasting many years, acceptance of Alvarez’ ideas is even now developing at the highest levels of the federal government, and significant funding--that proverbial silver bullet--has begun to come in for his Center for Marine Development and Protection.

“What I do today has an important meaning to me,” he says. “I loved the ocean in my early childhood. Then I tried to feed the world, but all of us have an empty feeling today when we see what is happening, leaving nothing left, to catch a fish, or serve it on a plate to our families, or simply to enjoy the beauty of marine life as we once knew it.

“I would feel terrible if I would plunge into our oceans and all this beauty would be gone. I would feel terrible if all this beauty were to disappear.”

Indeed, in all the world today, nobody is working harder to preserve that beauty for future generations than the young diver from the city of Acapulco’s movie star glamor days--Guillermo Alvarez--Mexico’s battle-scarred Lone Ranger of marine conservation.

|

IN THE BEGINNING -- The 1972 inauguration of the San Carlos tuna and sardine cannery at Magdalena Bay. Director General Guillermo Alvarez (second from right) is shown giving state and federal dignitaries a tour of the plant, at that time the most modern in Latin America. |

(Related Mexico articles and reports may be found at Mexfish.com's main Mexico information page. See weekly fishing news, photos, and reports from the major sportfishing vacation areas of Mexico including the Mexico area in "Mexico Fishing News.")

MEXICO FISHING INFO MEXICO FISHING INFO "WEEKLY MEXICO FISHING NEWS" FISH PHOTO GALLERY